Happy Halloween! It is spooky season, and every student in the country knows exactly what that means: all literature teachers with a pulse have just enthusiastically cracked open the works of Edgar Allan Poe for their classes once more. The American King of Gothic Horror has found his way into all of our lives, and that goes especially for his most popular work, “The Raven.”

A classic of not just American, but English-language poetry as a whole, “The Raven” has been studied and analyzed to death, to undeath, then to death again. The reason for this is that “The Raven” is a spectacular poem, easily one of the best ever written, but this constant coverage over and over in schools has watered down the effect of Poe’s ingenious verse. That alone is a shame, and what is worse is that when students ponder, weak and weary, over this same 108 lines of unforgettable lore year-after-year, the emphasis on literary analysis blinds them to the simplicity that makes “The Raven” so special. This issue is representative of a larger problem within the world of art—trying to pick something apart for symbolism until one cannot remember how it was put together in the first place. To illustrate this, let us, as is the Octoberly tradition, take another look at that famous midnight dreary.

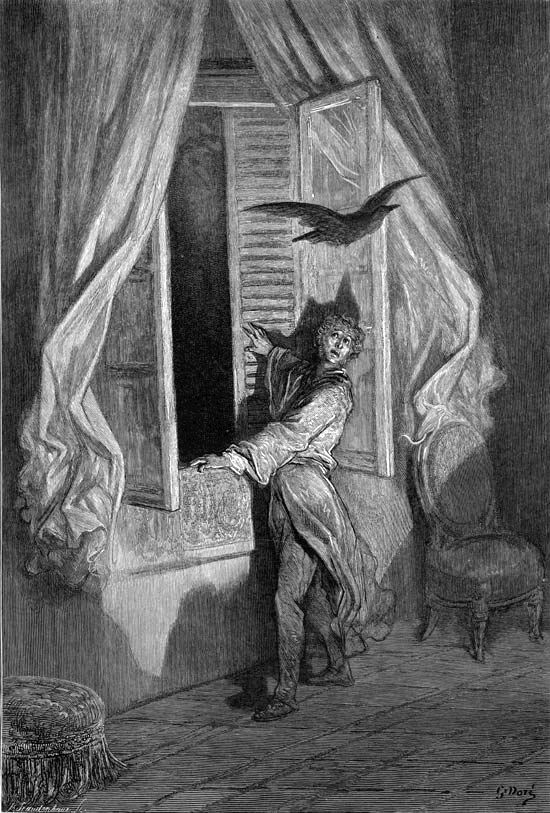

“The Raven” has a pretty simple plot. The narrator, grieving the loss of his beloved, is visited by a wayfaring raven who crows the word “nevermore” until the narrator is driven mad. Obviously, the most beguiling figure in all this is the titular raven itself. Since it is unusual for a person to have a bird fly into their bedroom and speak to them, this occurrence within the poem captures the attention. This means that when a young student is first met with the work, they are guided toward the raven as the poem’s central symbol. Students are taught to discover symbolism as a literary concept via study of that raven, which seems innocent enough on its own. The raven is definitely connected with grief and loss, but the ultimate problem with this widespread analytic practice is that reading the figure of the raven as a symbol simply isn’t how the story is meant to be engaged with.

Many are quick to turn up their nose to the notion that an artwork has a “proper” interpretation or any way that it was “meant” to be viewed, rather being in favor of the ambiguous principle that art is wholly subjective and that true meaning is defined uniquely by each individual. While such a principle touches on an important truth, that being the fact that each person has unique experiences and personalities which shape their interpretation of things, ultimately it must be accepted that artwork is born out of specific intention, and to remove it from this context is to render it meaningless at its core for the sake of the viewer. While the subjective interaction of each reader with “The Raven” serves to enrich its artistic value, the poem itself is trying to tell a quite specific story with a specific message, and it is most effective when read accordingly.

So then, how did Poe intend for his audience to interpret this work? What role does the all-important avian actually serve? In this case, this question fortunately has quite a definite answer. In the essay, The Philosophy of Composition, Poe lays out in no uncertain terms his reasoning for every aspect of “The Raven’s” form and content. He writes of the bird, “Here, then, immediately arose the idea of a non-reasoning creature capable of speech, and very naturally, a parrot, in the first instance, suggested itself, but was superseded forthwith by a Raven as equally capable of speech, and infinitely more in keeping with the intended tone.”

Notice how he phrases his choice to make the creature a raven. The choice was made to keep with the tone of the poem. A raven is a creature associated with dark themes like grief, but notably it was not ever Poe’s intention to use it as a symbolic representation of these things at all. The raven evokes grief, but the raven is not grief itself.

This difference may at first seem quite trivial, but its ramifications within the context of “The Raven” as a whole completely reframe the narrative and reveal the story’s true horror. A problem with a new reader encountering the poem is that it is not necessarily common knowledge that ravens can vocalize and form words like parrots do. This adds to the misconception of the bird’s role, as it may be considered supernatural in some way. This is, by the end of the story, what the narrator believes, however it is imperative that the reader see that he is incorrect. Earlier in the poem, the narrator decides that the bird learned how to say the word “nevermore” by hearing it many times from a previous owner. What Poe makes clear in Philosophy of Composition is that he is correct.

The raven in “The Raven” is not special, magical, or symbolic. It came through the narrator’s window because it was a stormy night. It crows “nevermore” because it heard that word many times, but, being a bird, has not the faintest idea of what it means. The horror of the story comes from that affliction which Edgar Allan Poe writes better than any other author—insanity. After dismissing the strange occurrence of the speaking raven entering his room, the narrator slowly lets his grief, which had been growing on him all evening, make him superstitious, and ultimately cause him to lose his mind. It is the narrator who sees the raven as a symbol of everlasting grief. He projects his sorrows onto an animal that, deep down, he knows is completely unintelligent. Therefore, the horror of “The Raven,” is found in the reader watching the narrator’s descent into madness as his overwhelming sense of loss makes him become pathetically superstitious, seeking the prophecy of a random bird in hopes that he may be relieved. What this means is that, with delightfully horrific irony, to read the figure of the raven as a symbol is actually to participate in the very same irrationality which drives the narrator to ultimate despair.

The horror of insanity, driven by the eternal loss of a beautiful loved one, is a much greater horror than a genuine haunting by a supernatural bird-demon. The reader can understand loss, can see themselves succumbing as the narrator does, can relate. The scenario has a deceptive inkling of reality, instead of being an overly abstract, cliche monster tale.

What does this mean in the context of art on the whole, though? How does this principle of a more simple explanation, in line with the actual intention by which art arises, relate beyond “The Raven” to all art forms?

Consider modern visual art: a banana taped to a wall, a signed urinal, a few paint splotches on a giant blank canvas. This abstraction rests upon the value of imparting abstract ideas, feelings, and concepts via strange or unusual imagery. There is a general consensus in the public, though, that work such as this barely qualifies as “art,” and even if it does, it does not hold a candle to the intricate works of the Romance or Renaissance periods. There is a yearning for artwork that is highly substantive and intentional, for the prominence of abstract work has overstayed its welcome due to the forced intellectual weight put upon the viewer for it to be valuable.

Such abstractions are blind to a core principle of artwork, which is that of making art for art’s sake. Surely art would be more palatable to all, more beautiful, even if those who are passionate about its study might recognize that there are times when the artist is not seeking to impart a great moral truth or deep philosophical revelation. Sometimes, the intention of art is just to look pretty, to be aesthetically pleasing. It is important to study how the tragic life of Vincent van Gogh influenced his paintings, but it is equally important to recognize that he made paintings because he probably liked the way that they looked.

“The Raven” isn’t some allegorical or deeply symbolic exploration of grief. Poe wrote it, according to him, with the intention of writing a poem which people would enjoy reading, and which made optimal use of poetic concepts and effects. He chose the figure of a raven because it was a sufficiently spooky animal. He wanted to tell a story about madness, and let his audience sympathize with and pity its main character. In all of these things, he succeeded. Sometimes art is that simple, and that makes it beautiful.

Leave a comment